Gunfire has affected almost every D.C. school over the past decade, risking profound and lasting impacts on children, an investigation by the News4 I-Team and The Trace Gun Violence Data Hub found

Gun violence is now the leading cause of death for all children and youth in the United States. In D.C., children were twice as likely to be victims or witnesses of violence compared to the national average, a study by the DC Policy Center found.

Gunfire affects nearly every school in D.C. Just two of the District’s 566 public and charter schools went 10 years without a single shooting nearby, a joint investigation by the News4 I-Team and The Trace Gun Violence Data Hub found. Science and residents’ own lived experience show the violence young people see, hear and have to cope with is taking a toll.

A 5-year-old girl named Shilo is in kindergarten at Ketcham Elementary School in the Anacostia neighborhood. Her mom, Sam, picks her up every day, then she only plays indoors. When the kindergartener and her mom hear gunshots, “I tell her it’s fireworks,” her mom said.

“I don’t want her to feel afraid,” she said.

An analysis of every shooting in D.C. from 2014 to 2023 by The Trace’s Gun Violence Data Hub calculated how close each shooting was to D.C.’s public and charter schools. The I-Team and the Trace examined shootings within 500 yards of a school, which is about four blocks in any direction.

The Trace’s analysis led the I-Team to the neighborhood around Ketcham Elementary, at Marion Barry Avenue and 15th Street. No school in D.C. had more shootings nearby in that time period than Ketcham Elementary, with 195 shootings from 2014 to 2023.

A little more than a third of these shootings occurred during daytime hours.

That’s 195 times that children studying, playing, eating or sleeping likely heard gunshots. Maybe they walked past a crime scene. Maybe they asked their mom a nervous question. Or they just swallowed the uncertainty and didn’t say a thing.

Encounters with gun violence are familiar to many D.C. children, said Advisory Neighborhood Commissioner Jamila White, who represents the area around Ketcham Elementary.

“They notice the police activity. They notice everything that’s happening. They have to walk through it. They have to drive through it. They have to experience it,” she said.

How shootings affect almost every DC school

Gun violence might be easier to try to solve if it just affected one part of D.C. or one group of children. But virtually every school and family is affected.

There are 566 D.C. public and public charter schools in the data the I-Team examined with The Trace.

Only two schools went 10 years without a single shooting nearby: Key Elementary School in the Palisades and Stoddert Elementary School in Glover Park. Just two out of 566 campuses.

“It’s a citywide issue that everyone is dealing with,” said White.

How shootings uniquely affect DC school communities

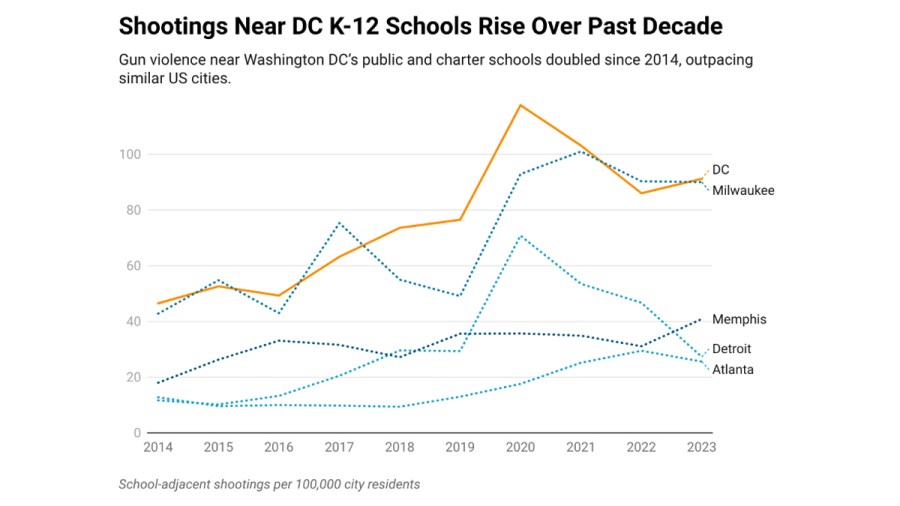

Data from The Trace shows shootings near schools increased in D.C. in recent years even as they fell in similar cities.

Gun crimes are down this year in D.C. compared to last year, but there still have been hundreds of shootings.

Virginia experienced about three school-adjacent shootings per 100,000 residents. Maryland had about nine school-adjacent shootings. In D.C., that number was 90 shootings per 100,000 residents.

Use this map from The Trace Gun Violence Data Hub to look up shootings near any school in the United States.

‘We should be upset’ by the effects shootings have on kids, pediatrician says

Studies show kids who see, hear or live near chronic violence have more anxiety, more health issues and lower math and reading scores. Proximity to violence in a community disrupts learning, a 2010 study by three Johns Hopkins University professors found.

“Increasing neighborhood violence was associated with statistically significant decreases from 4.2% to 8.7% in math and reading achievement, the researchers found.

Children coping with gun violence also can be faced with depression, anxiety, trouble sleeping, a feeling of hyper vigilance and an inability to trust people, said Jo Richardson, a gun violence researcher at the University of Maryland’s PROGRESS Center.

Pediatrician Dr. Woodie Kessel is Richardson’s research partner at UMD. He said he also has seen the profound effects gun violence has on children.

“It’s showing up in just the basic concerns about not retaining things, their cognitive ability, their attention spans,” he said.

News4 asked him, should we be surprised by that?

“We should be upset by it,” he replied.

The I-Team reached out to DC Public Schools numerous times asking for interviews with experts who could talk about how the school district handles the issues community violence creates for students. DCPS never agreed to an interview.

But gun violence isn’t a problem schools can handle alone, Richardson said.

“The school is not responsible for all the social problems that impact this community. It’s part of the fabric and DNA in this community,” he said.

A lack of investment to improve the community and a lack of follow-through by the adults in charge of cutting crime are hurting D.C. kids and changing daily life, White said.

“There’s so many parents who drop their kids off and it’s like, you live two blocks away. But they know that you’re not guaranteed to make it those two blocks,” she said.

How DC gun violence unequally affects school communities

The I-Team and The Trace found shootings near schools don’t affect every D.C. community equally. The 10 schools with the most shootings nearby account for 25% of all shootings in the time we examined. Nine of the 10 schools are Southeast D.C. Eight of the schools are east of the Anacostia River, in a burden these communities shoulder more than others.

“Communities are suffering from harm that could have been prevented,” said Richardson.

Nationally, 1 in 20 white students experienced at least one shooting near their schools in the 2022-2023 school year, The Trace found. One in four Black students experienced a shooting near their school in that period.

Searching for solutions

We know how to reduce the gun violence that has lasting effects on children, Richardson said.

“We understand the problems. There are so many people who are social scientists, behavioral scientists in the city, policymakers. We get it. And that’s what makes it so violent, is that we totally understand the problem to prevent it,” he said. “We’re responsible. We’re culpable in that.”

Five-year-old Shilo and thousands of other kids are growing up with the impacts of problems adults still haven’t solved.

“Sometimes when you’re sleeping, do you hear fireworks?” her mom asked her.

She nodded yes in response.

“A lot of them?” her mom asked.

“Yeah,” she replied.

“It’s heart-wrenching,” Shiloh’s mom told the I-Team. “But, you know, what can you do?”

When White recently asked middle school students for their biggest wish, the answer was heartbreaking.

“The number one answer from the youth was to stop the killings and kidnappings,” she said.

That plea came from 12-year-olds growing up in a part of D.C. too familiar with gun violence. White said Ward 8 kids notice a “lack of investment” in their community.

“They notice the lack of food. They notice people in need, people whose basic needs aren’t being met. People who are using substances to help cope,” she said.

Like White, Richardson also called for renewed investment in communities.

“We need to create an infrastructure where kids feel safe both within school, outside of school and within their households. But if we continue to engage in disinvestment, pulling back the resources, this will be the outcome,” he said.

When the I-Team reached out to the city for this story, a spokesperson for the city administrator said in an email: “The Bowser Administration is committed to building safe communities in all eight wards. That’s why we have invested historic funding levels for Anacostia and Ward 8 focusing on public safety, creating jobs, making housing more affordable, and building pathways of opportunity for our residents.”

Without greater investment in communities in crisis, residents and researchers worry we’ll be telling the same story again.

The I-Team asked White, how confident are you that if we have this conversation in 10 years, we’ll look back and say we got it right?

“I’m not very confident,” she replied.

Methodology

The Trace used data from the Gun Violence Archive and National Center for Education Statistics EDGE geographic datasets to perform the analyses that led to the findings. The Trace also used population estimates from 2010-2023 US Census Bureau data and D.C. public school profiles for school demographics.

The Gun Violence Archive tracks shootings through media and police reports, meaning the data provided likely underestimates the number of school-adjacent shootings that took place over the past decade. Nonfatal shootings are especially likely to be missed by GVA.

More than 30% of incidents do not include a time of day. Of those that do, most occurred late at night, between 6 PM and 2 AM. But the evidence of gun violence lingers long-term. Crime scene tape, blood, bullet holes, and other remnants of late-night shootings affect the emotional well-being of schoolchildren, Trace reporting found.

The project required intensive data cleaning because there is no standard format for how districts record school names. The Trace worked to clean the dataset and standardize all school names, but some schools may still appear with more than one name.